(c) Art New England Aug./Sept 2007

New Movements in Kinetic Sculpture

by Gwendolyn Holbrow

Arthur Ganson planned to become a surgeon, but somewhere along the pre-med path he took a detour onto the road less traveled.

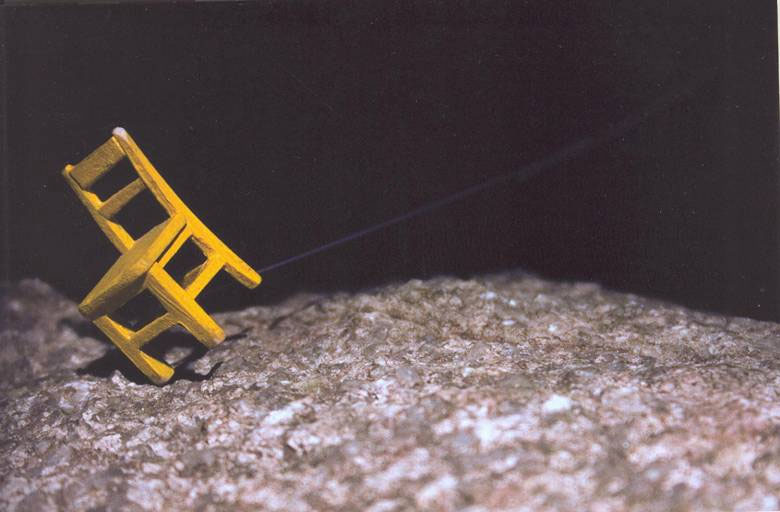

Arthur Ganson, Thinking Chair (detail 1), painted wood/mixed media, 26 x 30 x 30". Photo: Chehalis Hegner

Today, instead of scalpels and forceps, he wields pliers and welding torches, and the towers of boxes stacked in his gritty industrial studio have labels like Springs, Doll Parts, Air Hose, Webbing, Dried Leaves, Bronze Bushings, and Miscellaneous Wire Parts.

Over the past thirty years, Ganson has developed this assortment into a personal vocabulary of sprockets and pulleys, crankshafts and levers, from which he creates elegant and witty mechanical art.

Ganson's work owes a debt to the young Alexander Calder. Though best known for inventing the mobile around 1930, Calder made his first kinetic pieces for his miniature circus, Cirque Calder, in Paris during the 1920s. Formed from bent wire, cork, and scraps of fabric, and powered by pushing, turning cranks, or pulling strings, the dollhouse-sized animal and human figures performed their stunts with naturalistic motions and derring-do.

Like Calder,

Ganson employs bent wire, and much of his work is toy-like in size, but

the mechanical parts are orders of magnitude more intricate. Some pieces

are powered by turning cranks, others by electric motors in order to protect

their delicate mechanisms. Revolving gears and oscillating cams make a

rag doll stir restlessly, or transform scraps of torn paper into a flock

of migrating swans. An ostrich feather tenderly caresses a violin. A complicated

machine endows an inanimate object with a lifelike walking motion, allowing

a wishbone, a yellow chair, even a dry curled artichoke leaf, to stroll

contemplatively.

According to Ganson, these pieces are expressions of his own emotions

and experience. "Everything's a self-portrait, right?" he says.

But he is not trying to bring something inanimate to life. "I don't

want to pretend that these are anything but little bits of metal. This

is not magic," Ganson states firmly, adding, "It could be that

the little chair is the puppet and the mechanics is the puppeteer."

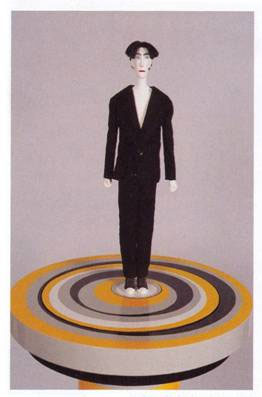

Pat Keck, Spinning Sleeping, painted wood/mixed media, 1994.

They turn over an hourglass, walk in their sleep, play musical instruments, and watch you through their glass eyes.

It was the

early death of punk performer and countertenor Klaus Nomi that inspired

Keck's first animated figure. "I so [much] did not want him to have

died, that it occurred to me that I should resurrect him," says Keck.

"It was actually like trying to raise the dead." And she did

exactly that, creating a life-sized reclining figure of Nomi, painted

black and white, that could sit up and lie down. Nomi's aesthetic, a theatrical

cross between Kabuki and carnival, continues to inform Keck's own.

Keck's most recent body of work, on view this summer at the Genovese /

Sullivan Gallery, spins on turntables, suggesting disorientation and lack

of control. The largest figure is Fortune, a pale four-foot woman with

yellow hair and a string of pearls, standing on a large roulette wheel

that visitors may turn. Other foot-tall mannequins whirl on nested spiraling

discs painted in her signature colors of black and white, red and yellow.

Much of her work explores "who's really in charge and who's pulling

the strings," according to Keck. "You

think you have control over what happens, but there are so many things

you have no control over."

Back in the 1980s, the World Sculpture Racing Society held kinetic sculpture races in Cambridge, MA. Ganson, Keck, George Greenamyer, and Bill Wainwright were all members, and the latter two are also acclaimed kinetic sculptors. Greenamyer's colorful wind-driven steel sculptures refer to whirligigs and American folk art, while making pointed social commentary, and his newest piece, The Merry-Go-Round of Hidden Agendas, was recently installed in the DeCordova Sculpture Park. Wainwright is best known for sparkling mobiles of light-refracting films. These artists, heirs of Alexander Calder, represent the side of kinetic sculpture descended from automatons, weathervanes, and mechanical toys.

As Calder and the Dadaists and surrealists added movement to sculpture in Paris, the constructivists were doing the same in Moscow and Berlin, but with a more industrial and architectural approach. The next generation of kinetic sculpture, including the self-annihilating machines of Swiss sculptor Jean Tinguely and the geometrically engineered abstract forms of American George Rickey, moved closer to the mechanical constructivist aesthetic.

Anne Lilly, There's a Certain Slant of Light, stainless steel, 23 x 12 x 12", 2007. Courtesy of Anne Lilly. Photo: Peter Harris.

Anne

Lilly's sculpture draws more upon this tradition. Her sleek futuristic

creations in brushed stainless steel produce complex movements from precisely

machined, yet simply shaped, cylinders, rods, and gears. "There are

almost no forms; it's just lines," she says. "What's interesting

to me is getting emptiness and matter kind of laced through each other.

There has to be matter to have motion." And

unlike most kinetic sculptors, Lilly may begin by creating a structure

to see how it moves, rather than imagining an outcome and working to manifest

it. Not always, though: "I had a desire to see something expanding

and contracting - something that would give me this swelling," she

says, which resulted in her current body of work.

Although Lilly focuses on negative space and employs austere geometric

forms and industrial material, the objects execute astonishingly graceful

organic gestures. Slender steel rods define planes and volumes, which

silently sway, expand, con tract, and pass through each other. The motion

is reminiscent of surface patterns on water, swaying tentacles, or a meadow

in the wind. Lilly calls her process "finding a system that results

in its own choreography." The viewer supplies the power by rotating

the base or geared cylinders, which Lilly considers vital. "You can

feel the mechanics, feel the piece responding," she explains. "I

think people are really starved for physical experience."

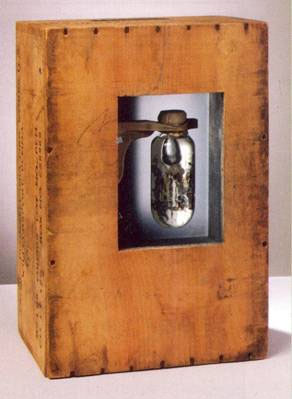

Steve Hollinger, Kwajalein, mixed-media (responds to sunlight). 18 x 12 x 10", 2006. Courtesy of Chase Gallery. Photo: Peter Harris

And his fascination is with time, rather than space. "I've read other kinetic sculptors were interested in space, and movement through space, and so on, and that's not something that I think about too much," he says. "Mostly I think time, and transformation or change."

Some of Hollinger's boxes, containing a elaborate rotating flipbooks or wheels of images with strobe lights, were on display last spring in the Picture Show -at the Photographic Resource Center as part of the Boston Cyberarts Festival. Other pieces depend on rotating polarized filters or tiny motors to animate them. Behind glass walls, butterflies flap their wings and bionic jellyfish propel themselves delicately through water when exposed to light. In Blue Heart, a moving piece in both senses of the word, light causes brilliant blue liquid to circulate through the spherical chambers and slender capillary tubes of a human-sized glass heart.

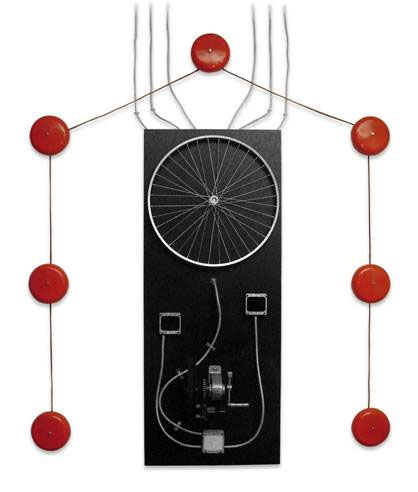

Ezekiel Borges Plateau, The Crank-O-Wank, bicycle wheels, bells, Film winder, electrical components, 60 x 24 x 5, 2007.

Before

conducting the tour, Salley inquires, "Have you any aversions to

stroboscopic lights? Foul odors? Loud sounds?" Once inside, the visitor

encounters all of the above, plus an oracle, a time machine, and other

kinetic works. Close collaborator Hans Spinnerman's Dream of Timmy Bumblebee,

a Patamechanical apparatus that extracts the dreams of bees and displays

them in glass jars, is the most intriguing individual piece. A genuine

gesamtkunstwerk [masterpiece of art], the Musee stimulates the five traditional

senses plus several more: the sense of proprioception, the sense of wonder,

and the sense of fun.

Gwendolyn Holbrow is

a sculptor, installation artist, and writer living in Framingham, MA.

She has been writing about visual art in New England since 2001.

(c) Art New England Aug./Sept.

2007